Africa needs the right strategies for adaptation and mitigation that meet the needs of the people, communities and further boosts our developmental agenda. Says Landry Ninteretse in an interview with Environment Africa Magazine.

Landry has been very passionate about climate awareness and community education on climate change. He also believes that only when everybody is aware of the impact of climate change can realistic solutions be provided. He also believes that solutions need to reflect Africa’s developmental challenges to ensure Africa does not become an experimental field. But those challenges need to be mitigated, not increased with unconscionable policies that are affecting Africa’s wildlife and heritage sites; polluting the environment with fossil fuels and for governments to stop contributing to the extinction of Africa’s bio-diversity.

The Africa Regional Director for 350.org, Landry has the upcoming global climate change focus in his sights and speaks on Africa’s climate change issues and where 350.org comes into play; even as the upcoming global climate change conference promises new hope…….

Interview by Nwosu Samuel

Excerpts:

EAM: Recently, China declared it would stop funding foreign coal investments. And this goes to the heart of one of the major issues pertaining to the Energy transition in Africa. With so much exploited natural energy resources and the highest rate of global energy poverty, how is this going to impact on Africa’s energy transition, and also on African economies?

LN: I think the announcement was made by President Xi Jinping at the United Nations General Assembly. We welcome the commitment by China, not to finance new coal plants across across the world, and to accelerate support for green and low carbon alternatives. I think that’s exactly what 360 has been doing over the years. We want world leaders, financial institutions, and others to commit to a just and rapid transition, which is based on renewables, which will contribute to reduce the catastrophic climate change that we’ve been in, and which is likely to get worse if nothing is done. So I think this is a great move in the right direction, and we do hope this is going to inspire the rest of big polluters globally. And we also hope this will spur African governments to reconsider some of the energy pathways that some of them have adopted, which we know is fossil fuel dependent.

EAM: What’s your take on the climate crisis in Africa juxtaposed against developmental expectations?

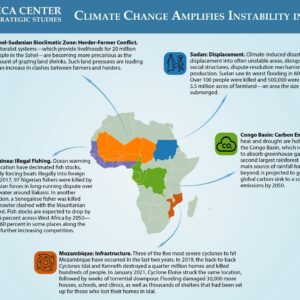

LN: The picture of climate change in Africa is unfortunately not a positive one. So we’ve been seeing increasing temperatures in sea level, almost across the entire continent. There have been very deep changes in rainfall patterns that have affected population, health and food production. There have been increased extreme weather events in different parts of the continent that threaten human health and safety, food and water security. Of course, there’s also the issue of economic development. I think, one of the recent examples that should be mentioned here is the island of Madagascar, which right now is confronted with a famine caused by climate change. This is a situation which has been well documented by the UN and humanitarian agencies on the ground. For the first time, a country has found itself in a situation where the extreme food crisis and insecurity they’re facing, which is now confirmed as a famine is caused not by conflict or other natural causes like what we’ve been seeing in the past, but an effect of the trauma caused by drastic climate change. This is a picture of the current status of climate crisis on the continent.

(Africa needs the right strategies for adaptation and mitigation that meet the needs of the people, communities and further boosts our developmental agenda…..says Landry Ninteretse)

(Africa needs the right strategies for adaptation and mitigation that meet the needs of the people, communities and further boosts our developmental agenda…..says Landry Ninteretse)

EAM: Going by official statements, it does appear that most African governments do not see Climate Change as an immediate threat but rather a global campaign to jump on to derive benefits. Do you agree?

LN: I do believe that the majority of African Nations governments are commencing to treat climate change as a serious issue. Why am I saying that? Out of the 55 countries of the continent at the moment, we’ve got 53 that have submitted their revised national determined contributions (NDCs), to reduce emissions. So Africa, in general, has made a great effort in driving the global climate agenda. And one of the reasons why, perhaps this issue hasn’t received the attention required, is that many of our governments are also confronted with other big priorities; whether they are fighting against terrorists, or they are trying to push for their development agenda, and other competing priorities, which tend to relegate the climate issue to the bottom. However, I think in the recent years, having seen the extreme weather event heating part of Southern Africa, Eastern Africa, and now in Madagascar; we’re seeing more leadership coming from governmental officials, indeed, to prioritize efforts that are meant to bring lasting solutions to this issue. Of course, there are still gaps in terms of capacity, capability, resources, technology; but we have to say that going by the level of ambition shown by submitting the revised NDCs, this is an indicator that the government are taking this issue seriously. They need to be of course supported by the the wider global community, especially the bigger polluters, which we know are historically those responsible for the current crisis.

EAM: You seem to indicate that African governments’ are not so much focused on climate change due to other more pressing challenges on ground. Is that a fact?

LN: Normally, the government is the protector of the people and have to take to take care of the people’s needs. And climate change, unfortunately, affects directly, the well being of populations in terms of food, shelter, in terms of health. So that’s why I think not prioritizing the climate agenda is a mistake, in my view. Because you can build the infrastructure, you can put up all the new technology that you want, but when a cyclone is likely to destroy those heavy and costly infrastructure; its a different ball game then. What we are saying is that climate has to be at the center of any development agenda, because it’s an integral part of development priority. And you can go far without integrating climate action into any development plan that is proposed. Yes, we understand there are other priorities; there is safety, there is security, health, and now, of course, the pandemic. However, that shouldn’t really relegate Climate change to the bottom of any development or political agenda.

EAM: With a lot of African governments talking about a just transition, how can Africa upscale this as an alternative energy transition model?

LN: The concept of ‘Just Transition’ came into being right after the Paris Agreement, right? I think one of the countries that we can say at the moment is championing this is South Africa, which is also the biggest polluter and carbon emitter on the continent. Through a number of research and scientific experiments, they’ve been able to design a pathway which shows that the country can still address its energy demand, can ensure safety for its population, and protect the ecosystem and still be doing well, economically speaking. So this is a model, which essentially not only addresses the issue of energy and climate change, but also looks at the needs of the population. Most of the time, when we are advocating for an uptake of renewable energy or a just transition to clean energy, most people tend to think that we are against the government.

But we’re saying that this transition is a module which can not only address, in a different way, the energy demand and needs that are there but at the same time ensure that it can provide a sense of safety and sustainability, especially for people that are at the center of the discussion.

You know, there are some assumptions in energy planning that large scale demand of industrial customers for instance, is required to support investment in energy infrastructure. And that approach is slowly losing momentum, because more attention is now been given to localize and resource efficient energy, options that are decentralized, that are community-led, that are based on solar, wind and other renewable sources of energy. So that’s the transition that we’re talking about. And of course, that comes with challenges.

This won’t happen easily. There are vested interests of the very big companies and corporations that have benefited and still benefiting from the fossil fuel industry. And they will do everything to block and oppose the just transition, because we are touching at the heart of their very dear interest.

So there is currently a kind of fight between those people and the population and the younger people today. As you may know, there is a another global mobilization campaign by the younger generation, and it’s called the climate strike; taking place all over the world, including Nigeria, South Africa, in Kenya, in Uganda, other parts of the continent. These are the people that are telling the fossil fuel leaders and the government that, ‘hey, we want you to care about our future. No, the model based on fossil fuels, has produced the exact crisis we are in now. However, we know that there there is a better alternative’; and that’s the current push for the just transition being undertaken by the communities, the younger people, the civil society movement, and whoever really is pro life and pro planet.

EAM: With 350.org’s years of insight, what would you say are the challenges limiting climate action in Africa?

LN: So I think in the last 10 years or so that we’ve been campaigning on these issues, we have kind of pushed the issue of climate change right to the point where it has become easily understood by ordinary people. We have tried to demystify the kind of scientific terminology and jargon that surround these issues to the point that everyone understands that climate change is caused by increased emissions. And if we were to tackle the crisis, you have to find better ways or activity that reduce the emissions, so we can live in a viable planet. A lot of people do refer to 350, but I’m not so sure everyone knows what it stands for. 350 means 350 ‘ppm’, parts per million; that’s the maximum level of carbon dioxide, which we can allow in the atmosphere for a viable planet.

Unfortunately, as we speak, I think we’ve gone beyond 450 ppm. So that means we are already in the red zone. So these efforts to cut down emissions to accelerate the just transition and do that in a rapid way, are meant to bring back those levels of ppm from 415 to 350; which is the safest level of climate change. Let me give you a kind of an anecdote, which is also a life experience.

In 2010. I was starting with 350.org and also I was teaching in a school somewhere in Uganda, East Africa. And I remember going for a class and teaching students about these issues. At the end, one of the students asked a question. ‘Excuse me, Mr. Teacher, so what can we do at the moment? And before I got a chance to answer, someone else screamed ‘Let us pray. Maybe we are in the last days’. That’s an example of 2010. Right? But 10 years later, we are seeing activists from Uganda. Now we have a generation, which has understood what this fight is about, and which is taking proactive measures, pushing the leaders to take the right decision.

You can see the shift, the change, and the level of awareness, which wasn’t noticeable 10 years ago, where people were still thinking they were heading to the end of the world. So that’s some of the effort that we have at 350.org tried to make public. You don’t have to be a scientist, you don’t have to be a doctor or someone who is specialized in this industry to take action,. Even a mother, a pastor, a student can be part of this movement. And I think change.

In terms of the challenges that may be affecting or causing some of the limitations by government, I think, again, we can’t generalize but these issues are unique challenges and priorities. But in general, when you look at the way different governments have been tackling these issues,you’ll find over the years that there has been a consistent and constant realization that if government don’t protect these issues, then the crisis is going to affect the entire development agenda. And I think the number of countries that have ratified the Paris Agreement is an indicator. And there has also been a realization that there is no future in the fossil fuel industry. So far, because of the communities rising up, you know, from Benin, Senegal, to Nigeria etc, to challenge fossil fuel projects, the government are now considering their energy policies. The challenges remain, because again, not all governments have got enough capacity and capability to implement the policies they want to. There are gaps in terms of resources, there are gaps in terms of technology, there are gaps in terms of scientific knowledge that could allow these changes to occur in each country that we’re talking about. Yes.

So that’s why I think during this global platform, like the Conference of Parties on climate change, you will hear African leaders being extremely vocal on the finance element, and technology transfer, because these are the key factors that can allow the implementation of the reforms that are being put forward. So these are some of the key challenges. There have been a realization and understanding which is a positive, we appreciate that. However, when it comes to climate finance and technology transfers, yes, gaps are real.

EAM: 53 African countries have ratified the Paris Agreement. At the same time, several have joined the energy charter; and still several investing in coal and oil exploration. How do you marry all these against the energy transition target?

LN: When you look at the picture right now, especially with some of the oil and gas producer countries you may find a situation which seems to be contradictory. On one side, countries are pledging to cut down emissions, but at the same time, they are accelerating the oil and gas industry. So my belief, and my analysis is that the answer lies in the just transition, which we know won’t take effect immediately. It’s a process, which can take between 10 to 20 years or more, to the point where this countries can put up a national plan, and draw up a timeline on how they’re going to be accelerating or increasing the uptake of renewable energy. Because again, at this moment, it would be unfair to ask a country like Nigeria or Angola, not to mention Algeria to immediately shut down their productions, because we know there are other countries out there that are still producing this. I mean, the exact same fossil fuels, right? That’s why there is a negotiation happening. It’s not something which can take effect, like right away. But we wanted the minimum commitment to gradually phase out the oil and gas industry and being supported, and also knowing what others are doing. Because, again, I think Africa is not the biggest polluter. So it will be unfair to put a kind of pressure on our countries, while we know that others are maybe not doing much. So I would say then, just to sum up that the answer lies in the a just transition, which kind of needs a realistic timeline to be able to phase out the current fossil fuel industry, and at the same time, accelerate or increase renewable energy.

EAM: Can we see a situation where Africa develops a regional Just Transition framework that takes into cognisance the realities of energy access and poverty in Africa?

LN: So it’s not an easy fight to be realistic. But I want to come back to the announcement by China, committing to not fund or build any new coal plant overseas is an encouraging one. The announcement by China, for instance, is going to have an effect on the plans of other countries that may still want to venture into exploration.

I just want to highlight the challenge two companies operating in the Great Lakes region of Africa, in the Congo and Uganda, where lead oil exploration activities are taking place, are undergoing. Some of these projects were meant to start in a few years. But however, because of growing evidence that we can’t afford to explore and exploit new oil or gas fields, we’ve seen a number of banks now distancing themselves from financing these projects. And I think this is an example of climate investment ambitions and real action. This is a commitment to be on the right side of the issue. So it is not okay, to be actively seeking to explore and exploit new fossil fuels, while at the same time you are committing to resolve the climate crisis through the Paris Agreement. I think there are hard choices to be made by the government.

And as I say, the old model which hinges on large scale energy infrastructure to attract foreign investors is no longer applicable. The approach that we are actually promoting and encouraging is the one which is localized, resource sufficient, community led; because at the end of the day, that’s what can satisfy the needs and priorities of the people.

EAM: With clean energy solutions becoming more popular and desirable, how do we manage the varied disjointed frameworks to ensure that we don’t turn into a depository of global activities but promote realistic solutions that are viable and sustainable for Africa?

LN: So we know that energy is critical to development, right? And we have an urgent need to start managing the just transition which is not based on fossil fuels, but rather on renewables. And within the last five or 10 years, there have been a dramatic decline of renewable energy prices globally. That’s a fact. That’s actually what’s been encouraging the belief that the just transition is possible. Because the price of the renewable energy everywhere on the planet is getting lower by the day. So that’s something that the government could really tap into. Like how can we leverage on these opportunities to make sure that our energy systems are more sustainable? Are more responsive to the needs of the people? And also, most importantly, contribute to protect the ecosystems and the planet. It’s really a matter of leadership, and making the right choices at the right moment. And also applying with bold ambition and determination, this policy and strategy, and be in a position to inspire the rest.

I’m very sure that if the just transition strategies and action plan being put together in South Africa, for instance, or other countries are successful, they’re likely to influence neighboring countries. So there’s a sort of context here as countries like Botswana, Malawi, Zimbabwe, Zambia will be able emulate such a plan or be encouraged by what’s happening. If Nigeria puts in place a realistic just transition plan to phase out its dependence or to break the addiction to oil and gas in the next few years; this is something which could inspire countries around like Ghana, Benin, Cote d’Ivoire, etc. So I think it’s just a matter really, of understanding the issue at hand, taking a bold step and, you know, be determined on implementation with the hope to inspire others to emulate what is coming out as a success story.

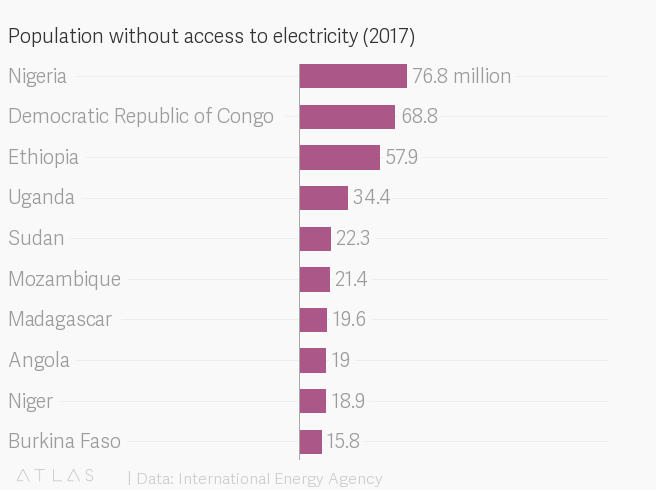

So this is where we believe Africa will be able, actually to address the energy gap and energy poverty. We know that today, over 6 million of Africans don’t have access to clean source of energy. And that gap won’t be made by the old classic kind of energy infrastructure, which is based on fossil fuels or big hydro. That’s why decentralized sources of energy are desired if we want to address these issues in the long term.

EAM: With 350.org having been involved in Africa-centric activities, what interventions or contributions has your organization brought to the mix?

LN: As we speak, right now we are running campaigns and projects across the continent. I can tell you that there are so many people that are mobilized exactly on this issue of a just energy transition; stop burning new fossil fuels, and coming up with the right strategies of adaptation and mitigation. So this is part of our daily work.

But there are a few key battles or campaigns that we’ve been working on. Firstly, is the fight to ‘Stop nuclear plants on the continent’, right? We are proud to have contributed to Resistance Calls on Kenya, in Zimbabwe. These are the key specific examples where we’ve worked with communities as allies and our supporters globally to make sure that these countries don’t get kind of locked into a new kind of coal addiction and we are very proud of that. At the same time we know that these countries also have need that have to be satisfied. So we are working with partners to see how we can lobby and work with the officials and other development partners in those countries to make sure that there is a right energy transition that can still meet the needs of the people and the communities and further boost their development agenda, but not by funding fossil fuels. That’s one of the examples.

And we have other battles like I said happening in the Great Lakes region of Africa; to combat and stop oil exploration in some of the very preserved rich ecosystems like the nature park in the Congo, or the parks that are located in the western part of Uganda. This is a unique region and area rich on diversity that are threatened by oil exploration. We continue supporting and working together with partners, unions, communities affected by mining activities to make sure that the just transition agenda is a one which is inclusive, which is diverse, which is centered on peoples’ and community needs. And which doesn’t satisfy the growing appetite of the mining and the corporate industries. I think these are some of the biggest campaigns that we are supporting regionally.